Addressing cholera in Lebanon: “Vaccination and access to clean water are essential”

8 December 2022

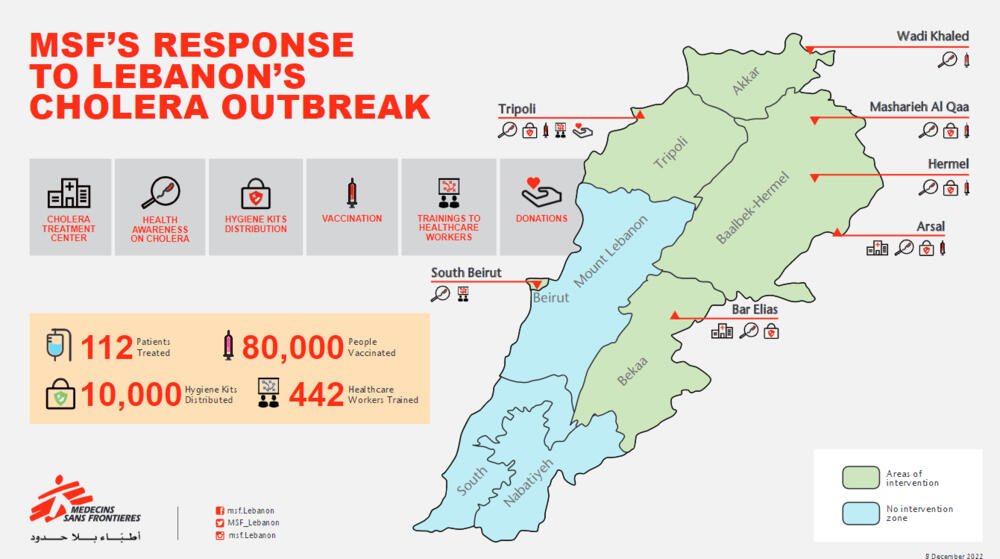

Lebanon is battling its first outbreak of cholera in three decades. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) provides hygiene kits, vaccinations, oral rehydration points, in the Bekaa valley, north and northeast of the country areas with the highest number of confirmed cases in addition to medical care in two cholera treatment centers in Bekaa Valley. By the end of November, MSF in collaboration with other international and national actors had administered nearly 600,000 cholera vaccines in an effort to curb the outbreak. But limited access to safe water and proper waste management networks in the country have created an additional barrier to containing the spread of the disease.

MSF’s head of mission in Lebanon, Dr. Marcelo Fernandez, describes what he saw on a recent visit to Bekaa Valley.

Why is Lebanon facing an outbreak today?

Cholera—like many infectious diseases—is preventable when sanitary and public health measures are in place. Caused by a water-borne bacterial infection, cholera is transmitted through contaminated food or water, or through contact with fecal matter or vomit from infected people. However, the disease is unlikely to rapidly spread in places where there is adequate water treatment and proper sanitation. In Lebanon, these conditions have been compromised as the country faces one of the worst economic crises in the world, creating an ideal environment for the disease to spread. The water, waste management and electricity networks in Lebanon are old and not properly maintained, causing them to leak. The resulting inadequate water supply and water treatment infrastructure allow waterborne disease to surface, including cholera and Hepatitis A (which was recorded in Lebanon’s second largest city, Tripoli, in June 2022). These outbreaks are a symptom of a collapsed water system, which has been impacted by compounded crises in the country.

Why is the cholera outbreak in Lebanon so worrying?

Access to vaccines and clean water is essential to curb a cholera outbreak. The current economic and energy crisis—which has seen increasingly frequent electricity cuts—in Lebanon has further strained access to safe water and sanitation services. The water pumps that supply water to specific areas recently stopped working due to multiple power outages, meaning people have to rely even more often on unregulated private water trucking companies for their water supply. Impacted by the financial crisis people who are unable to afford private water trucking supply—particularly those in remote and neglected areas— are relying on polluted rivers and ponds to cover their water needs. Already old, wastewater networks, are not being maintained leading them to leak into camps and households.

A preliminary assessment done by our teams in the north (Wadi Khaled) and northeast (Arsal, Mashrieh Al Qaa & Hermel) of the country, in early October, showed that water sources – whether water trucking, wells, or water networks) lack chlorine residual indicating a concern over the quality of water reaching the people. Usually a sufficient amount of chlorine is added to the water to inactivate the bacteria and some viruses that cause diarrheal disease by that water is also protected from recontamination during storage. It is an essential element to maintain the quality of water through the distribution network.

In parallel, there is a severe shortage of medical supplies and diagnostics. The health system is increasingly reliant on donor support, which will reduce its capacity to rapidly and adequately respond if cases continue to spread across the country. Because of the economic crisis, most people can’t afford healthcare.

All of these factors contribute to the rapid spread of cholera and hinder its containment. It even makes it hard for people to implement prevention measures.

What are the required measures and actions needed to curb the outbreak?

To be able to effectively curb the outbreak, it is crucial to enhance cholera prevention measures, and vaccination and clean water are two critical elements to this. If no meaningful actions are taken to ensure people have proper access to safe drinking water and sanitation services in the country, we can expect cholera and other waterborne infectious diseases to resurface regularly in Lebanon.

Now that a national vaccination campaign is being rolled out, hospitals are prepared with medical supplies, healthcare workers have been trained, and health awareness outreach has been done within communities, we have the opportunity to really focus on the prevention arm of the outbreak. However, relevant actors must ensure access to safe drinking water and sanitation services to address the root causes of this health emergency.