Innovation in Honduras: Fighting dengue with mosquitos

14 November 2024

The sky over El Manchén is as blue as ever. This suburb of Honduras’ capital is still bustling, with people jostling to get to work and cars honking in the heavy traffic. To the naked eye, this densely populated area seems much like it did a year ago. But one Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) team has been working hard to make a microscopic change that could save lives.

A recent test found that eight out of ten mosquitos caught in El Manchén carry Wolbachia, a harmless bacteria that’s found in over 50% of insects. One year ago, almost none of the local mosquitos were.

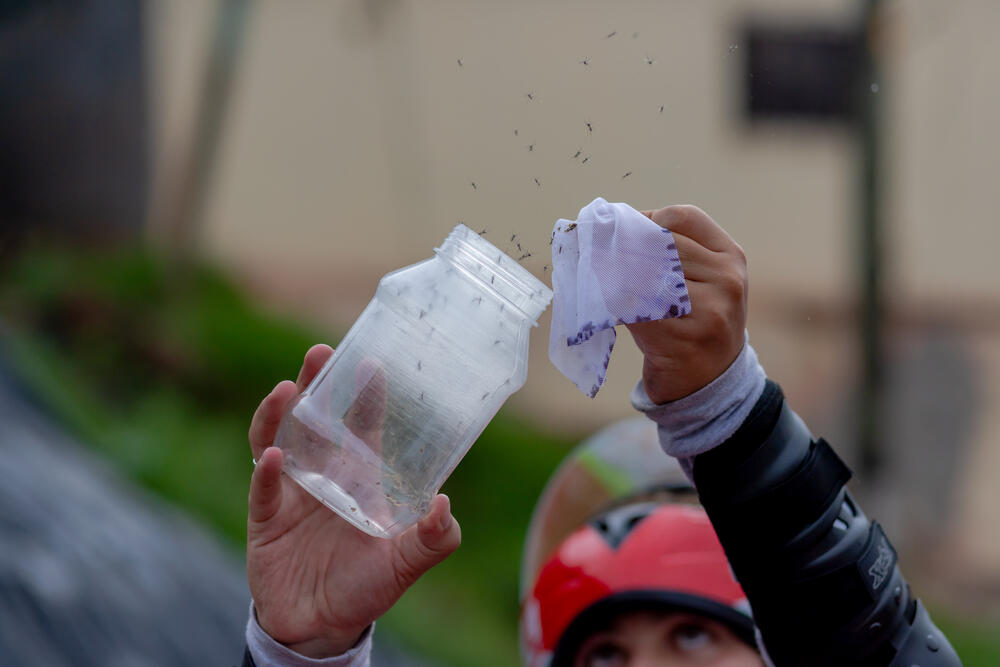

This matters, because Wolbachia dramatically reduces the likelihood that mosquitos will transmit diseases like dengue fever, a potentially deadly disease which affects an estimated 100–400 million people worldwide each year . The team at the MSF Arbovirus Prevention Project released over eight million mosquitos deliberately infected with the bacteria were released in El Manchén last year. Their hope was that the mosquitos would thrive, reproducing and passing Wolbachia down through the generations, radically reducing the rate of dengue in the area.

However, there was a lot that could go wrong. “As we continued to release mosquitos, this meant there were more and more of them in the area, which caused distress to the local communities. At the same time, another dengue epidemic broke out in the capital. This made it more difficult to approach people about dengue, but by engaging them directly in the activities, we were able to do everything as planned.” said Edgard Boquín, coordinator of the project.

“We’ve been working in partnership with local communities, Honduran health authorities, the National Autonomous University of Honduras (UNAH) and the World Mosquito Program (WMP). It’s been a real team effort! This is the first time that MSF and the WMP have worked together on arbovirus prevention like dengue. Our strength in community involvement and the WMP's technical expertise complemented each other to make this a reality,” adds Boquín.

So has it worked?

El Manchén previously had among the highest rates of dengue fever in the city. However, in the past year there have been fewer cases than in previous years, and lower rates compared to other areas of the city.

“It’s still too early to claim victory,” Boquín says cautiously. “We tested 294 mosquitos in September, and we were really pleased that 85,7% were carriers of Wolbachia. However, these are preliminary results. In the first quarter of 2025, definitive tests will be carried out that will tell us to what extent this strategy has served to reduce the impact of dengue in El Manchén”.

Although he’s careful about showing too much excitement too soon, Boquín is hopeful. “This is undoubtedly promising,” he says, with a smile of satisfaction.

“If we continue this path, the Wolbachia method will be a positive tool to reduce dengue in the country. For a long time, we have seen how people have suffered from dengue but now we hear positive stories from the community that something is changing after the Wolbachia release; this gives hope to those who has experienced dengue or has seen someone close to them get sick.”