The Philippines: Five years of medical care for Marawi siege survivors

24 January 2023

It has been five years since the siege of Marawi displaced 98 per cent of the population of the southern Philippines city. Since the conflict, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has provided care for the people of Marawi and adapted our activities to the changing needs of the communities.

In December 2022, with the acute and post-emergency phases of our medical response over, MSF decided to close our project and hand over our activities to local health actors.

As activities come to an end, MSF patients and staff look back at five years of the Marawi project.

Life under decades of conflict and the Marawi siege

In the south of the Philippines lies Mindanao, a large island whose history has been marred by conflict for more than 50 years. Clashes between armed groups and the Philippine army have resulted in frequent violence. The city of Marawi is located in Lanao del Sur province in the Bangsamoro Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao (BARMM). The region has long struggled with the weakest health and economic indicators in the country.

In May 2017, two groups affiliated with the Islamic State seized Marawi, leading to a conflict with the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP). The fighting lasted five months, forcing more than 350,000 locals from Marawi and nearby municipalities to flee their homes. The clashes completely destroyed the city centre. "Marawi’s city centre, called ‘Ground Zero’, looked like pictures in the news from Mariupol or Mosul," says Aurélien Sigwalt, head of mission for MSF in the Philippines.

"I only really got sick after the Marawi siege because of our problems and fears,” recalls MSF patient Rasmia Magompara. “We had evacuated during the Marawi siege, with no belongings, no money. All we had was what was in our pockets and what we were wearing. With all our fears and problems, every time I heard a motorcycle, I thought it was a helicopter. Next thing I knew, it was morning, the sun had risen, and I hadn’t been able to sleep."

Supporting those displaced by the siege

By July 2017, MSF launched a project to assist people who had been forced to flee their homes in the fighting. MSF provided support with water and sanitation and psychological first aid for a total of 11,000 people living in evacuation centres in Marawi and the surrounding region.

Dr Natasha Reyes was the emergency response support manager at the time. “The first part of MSF’s response was to make sure people had access to free and clean water,” she says. “We distributed jerrycans and water purification tablets, repaired pipes and toilets, put up showers, and built reservoirs so communities could store their water.”

“Our other priority was mental health support. We organised psychosocial activities for the children. The stress of their parents also affected them: our teams organised play therapy to make them feel like kids again. We also held one-on-one sessions for adults and children who needed it.”

From observer to health promoter

Amelia Pandapatan was one of the displaced people who received support from MSF in 2017. “I saw MSF going to the shelters, doing a mental health program, giving out hygiene kits,” she recalls.

When she heard that MSF was hiring, she applied to be a health promoter right away. She recalls the challenges they faced in 2017: “The medical team started with a small group of local staff. We had one doctor, one pharmacist, two nurses and one health promoter. We managed to do our daily activities in the clinic, but it was a bit of a challenge. Health promoters would help with registration, checking vital signs. I became a translator between doctors and patients.”

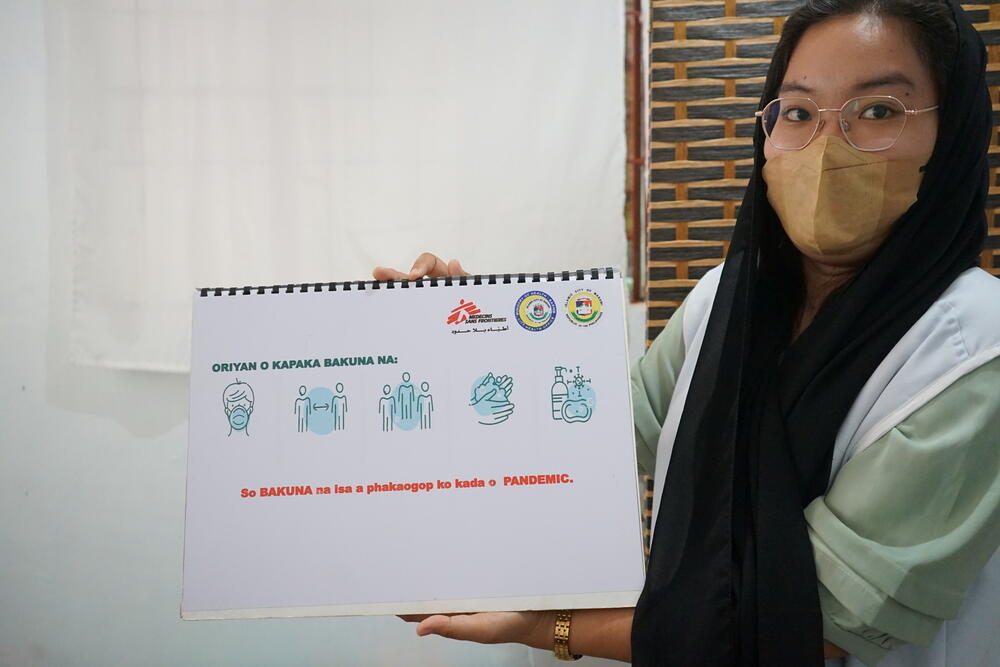

Considering the region’s history of weak health indicators, the work of a health promoter is critical, and this is something Pandapatan can be proud of. “As health promoters, we deliver health education to our patients and community. I think that’s one of our achievements, seeing our patients with the ability to manage their own health.”

Disrupted lives and health needs in the aftermath of the conflict

Slowly, the situation stabilised in Marawi. Displaced people moved from tents to evacuation centres and temporary shelters, with the last families moving to shelters in January 2020. Due to the challenges in rebuilding the city, many Marawi residents have been unable to move back to the city centre, remaining in shelters until now. Many have not been granted a permit to return home, or they face challenges in rebuilding or repairing their houses due to financial constraints.

Of the 39 health facilities in Marawi and the surrounding areas, 15 were functioning by 2020; the others had been destroyed or were unable to reopen. MSF supported the rehabilitation of the Marawi Rural Health Unit (RHU) and City Health Office (CHO) facilities and clinics, as well as clinics in the city’s three shelters.

In 2018, MSF started working in clinics in three transitory shelters, as well as in the main CHO, providing free consultations and free medication for primary healthcare.

As the emergency needs decreased, health issues that persisted long before the siege resurfaced. Hypertension and diabetes have since ranked among the 10 leading causes of mortality in the Lanao del Sur region, which is why MSF started a program focused on non-communicable diseases in 2019.

In addition to providing consultations and medication, MSF health promotion staff also conducted patient education sessions, where patients learned about non-communicable diseases and what they could do to stay healthy. “When MSF started working at the clinic in the Rorogagus shelter, my wife and I were very thankful because it was close to us, and we received free medicine,” says patient Said Abdullah, aged 76. “We followed the advice given to us. I've been exercising and avoiding foods that are not advised for those with high blood pressure, and now I'm much better. The daily dizziness is gone.”

Between 2018 and 2022, the MSF teams conducted 30,000 primary healthcare consultations and over 10,000 non-communicable disease consultations in Marawi.

Handing over medical activities to local health actors

“Five years after the siege, the acute and the post-emergency phases are over. The Marawi health authorities have a better capacity to manage non-communicable disease patients, and to provide primary healthcare to the people of Marawi,” says Sigwalt. In anticipation of the project closing, MSF has worked closely with the Marawi CHO to enhance local capacity to support health needs and has donated medicines to support the continued care of patients.

“All I can say is that we hope the Marawi siege never happens again, and for Marawi to be peaceful.”

Patients who have been in the care of MSF’s non-communicable disease program have gradually been transferred to the CHO over the past few months. Sarah Ambor, MSF health promotion supervisor, explains: “We conducted monthly meetings with the CHO to provide updates regarding the patients, their medication and their needs in order for the patients to continue to receive the care they need.”

In 2021 and 2022, MSF also implemented a mentorship program for 67 RHU staff members in the province of Lanao del Sur to transfer technical skills and knowledge on the management of non-communicable diseases.

Five years since the siege, the city of Marawi still bears the scars it caused. Many structures remain in ruins in ‘Ground Zero’. Patient Said Abdullah’s wish is simple: “All I can say is that we hope the Marawi siege never happens again, and for Marawi to be peaceful.”

MSF remains in the Philippines, running a tuberculosis program in Manila, and will continue to assess the support needs of other health organisations in the country in 2023.